Futuredebt - 2 - Like oil on silk

I’m releasing a novel called Futuredebt across 2024, letting it go one chapter at a time. The first chapters are available for free, but you’ll need to join my Patreon to read later chapters.

Click here to go back and read from chapter one.

How long do you stay when you know it isn't going to last? The future has told Kerry the man she loves today will not be the one she marries in the future. Now she has to decide what she does with that knowledge. Meanwhile, at the other end of society, Fi finds herself struggling with a world that seems to be working against her, pushing her into the heart of a revolution plotting to bring the system crashing to its knees. Futuredebt is a story of free will, self-determination and how small acts of kindness can be a catalyst for change.

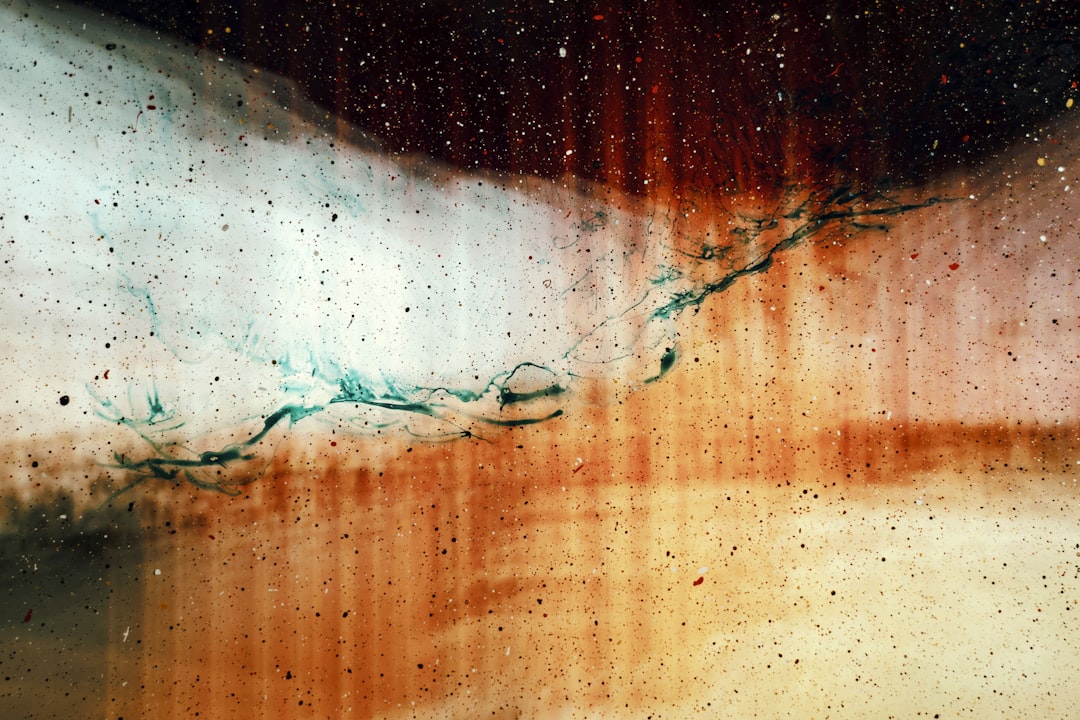

Like oil on silk

John drops her at the studio where she will sit herself down in front of yet another self portrait. Dark hair, shoulder length. Thin nose. Wide eyes. It will share all of its features with her and none of its soul. She picks up a pallet and refreshes her paints, her brush skipping between colours until she makes a blend almost, but not entirely, the shade she intends. She checks the colour against the flecks caught in her cuticles and picks up another pallet. She will spend another hour doing this before she begins: mixing, checking, failing, starting again. The flecks taunt her every time.

Her fingernails are much like yours: gnawed down to nubs, edges raw and serrated like knives. Or, at least, they are how your nails used to be. They say fingernails continue to grow after you die but that isn’t exactly true. The flesh shrinks back, giving the appearance of growth, but the nail is as dead as the rest of you.

The studio is a shared space at the back of the Central Gallery, bright and airy and accessed through a double fire door at the back of the Mormont Exhibition Space. This was the same place you used to peer into on your way to the Jeremy Bentham Room, gazing at the real-life working artists. It was a novelty. There were once a few dozen of them sharing that marvellous light from those vast overhead windows, but then there was Covid and Brexit and the FDF and for some unknown reason most of the other artists never came back.

There’s six of them now who share the space, trying their best to justify its existence to the gallery management. Everyone there has to fight or, more commonly, increase their rent to keep the place going and each person who drops out makes it harder to manage for those left behind. Making art is not a lucrative business model. Grants have dried up and Etsy has become so competitive there’s few sellers who haven’t been bought out by foreign sweatshops, eager to pay for login details and a history of good reviews to give their mass produced reproductions a glossy veneer of credibility. You can make more money from selling your reputation than you can your art.

Each resident’s mess is separated from their neighbours’ by a row of upright display boards. These fragile partitions are all that divide the creeping degrees of chaos and they often buckle and tip from the strain. Every artist’s production history is crammed into those spaces. You can remember when they opened up the place to the public to give them a peek at these one-day masterpieces piled waist high. Unframed. Sick with potential. A woman in front of you in the queue baulked when she was told the asking price for a framed seaside. You remember how the artist’s face dropped, wishing you could reach in and tease out the years of practice and string them up like bunting to decorate the place.

Ikea has ruined us.

If it wasn’t for John, Kerry would already have given up the studio space. You’re lucky to have it, he will tell her every time she begins to lose heart. It will buoy her up, show her she is doing the right thing with her life. And he’s right, after all. She is lucky to have it.

Look at her now, plastering away at her own face on the canvas.

Her phone is plugged into the socket next to the sink, sitting on top of a pile of rejected work, inches away from a watery grave. The bottom sheets of the pile are stained with splashes from the taps. The water pressure in this place is a joke, turned up to ensure there is always enough stored in the sprinkler system to douse any fire - so much so that you should never trust a man returning from the toilets without splatter marks across his front.

She works steadily for two hours and then drops her palette on the side and sets about cleaning her brushes, pulling on an old set of marigolds before filling the air with the scent of turpentine.

She thinks of you as she swirls the brushes and turns the white spirit murky. Everything you had been wearing that morning seemed out of place. That beautiful sage green dress, a lace strip patterned like frost around the bust. Proper evening wear, apart from the shoes. Bare feet, just a pair of tan tights ripped around the toes. She only saw the details after you lay broken on the concrete bleeding rivers into the gravel soak-away around the building’s base but now she imagines them there as you fell. She has perfected her image of you, crystallizing the moment in the smoke of her memory. Mid-air. Falling forever.

I gave you that dress

remember?

The brushes are left to dry in a pewter flagon, arranged like a bouquet of flowers, bristles to the sky. She strips the gloves from her hands and begins washing the smell of white spirit from her skin. When her phone buzzes on top of the pile of papers next to the sink, she turns off the tap but the hand towel has disappeared again. She huffs in annoyance and jabs at the screen with her elbow, sending the phone sliding around on the paper like a hockey puck on ice. The papers slip and an avalanche of unfinished faces scatter across the floor, the phone swooping down after them until the power cable pulls taut and bungies the thing to safety an inch from the tiles.

She wipes her hands dry on her clothes but the buzzing cuts off before she can get control of the situation. A moment later and a message flicks onto the screen. It is her sister, fussing over final arrangements for tonight’s party. She has already begun drinking, judging by the state of some of her more incomprehensible autocorrect substitutions, several messages sent in quick succession. Kerry sets the phone back down on the side without replying and turns to look over the fallen pictures. Her own face stares up at her in various states of completion, shattered like glass.

A voice scuttles in from the corner of her little space: You OK?

A man scratches his fledgling beard, one arm hitched over the display board. He tips his scrappy white cap back up on his head and surveys the scene.

Everything just slipped, she says but this isn’t a lone occurrence. Again, she admits.

He grins one of those insider smiles that is more awkward than intimate. It gives the impression that here is the sort of person who creates sculptures of pop icons in classical poses, equipped with outlandishly oversized genitalia and he will be more than happy to show them to you.

Let me give you a hand, he says.

No, Andrew, please don’t, she says. I’m fine, honestly. But could you… She lifts a finger to point at where his fingers crush the articles she has pinned to the partition for inspiration.

Oh. Right. Sorry, he says, smoothing down the clipping. She lifts up a pile of papers and rests them back up to the side then sits cross legged on the floor to collect the rest. He stands there, watching.

You know, he says, when you’re done here I was thinking of going out to grab a bite to eat if you’re up for it.

For a moment she stumbles over her response, knowing she has to navigate herself away from the unintended undertone in his suggestion. The two of them are among the youngest artists renting spaces at the studio and they are awkwardly aware that the rest of the residents think of them as artistic breeding stock to secure the next generation of little dreamers. Even dragging John along to the studio was not able to dispel the illusion of rumours in her mind.

He recognises her hesitation.

It would be me, you, Janet, Gerard and I think Tom said he was up for it, he says, setting out the boundaries in order to quash any scandal in his invitation. A little studio social, he says.

She neatens the corners of her papers in her lap, but the sizes are different and they don’t line up. Thanks, she says. But my sister has this thing tonight. It’s a divorce party. I’ve got to pick up a few things beforehand, so… Maybe another night?

OK, he says and points to the easel where her picture sits drying. Is this new, he asks.

Same old, same old, she says, pulling herself up and dumping her gathered faces on the countertop. She flicks through a few, evaluating which to keep and which to toss into the abyss. They’re mostly impressionist in texture, the same Yuko Saeki pout and hardline brush strokes in every one. She tries to assemble them back into chronological order but the timeline is untraceable.

I like the, er… colours, he says, pointing to the painting. His fumble is obvious and he knows it. So does she. Another self-portrait indistinguishable from the others and they both know it. He stuffs his hands into his pockets and tries to change the subject.

How’s John?

He’s good.

Good, he says.

He glances back at the painting and she swears she sees him wince. She sits on the floor and gathers in another set of faces.

Well, he says. If you’re OK here then I’m gonna go back. Give me a call if you change your mind about tonight.

He pauses a second and sucks air through his teeth, raises his eyebrows in a departing acknowledgement of the awkwardness of the whole affair and sets off wandering back to his partition. She waits until she hears him routing in his scrap box before she gets up, leaving the remaining pictures on the floor.

Resigned, she cuts her newest canvas from the frame and begins to roll it up, knowing full well that the oils will set like glue if it dries like this, preventing it from being unrolled without damaging the picture inside. The canvas becomes a hollow tube through which she can see the practice pieces scattered on the floor. She tests its rigidity by tapping it against her palm and seals it with a length of string. There is a place for it among the rest. Years of work, stacked like the dead sea scrolls in a specially made shelving unit. She sighs and slots the canvas in alongside the rest.