Bible

A post-belief perspective

A post-belief perspective

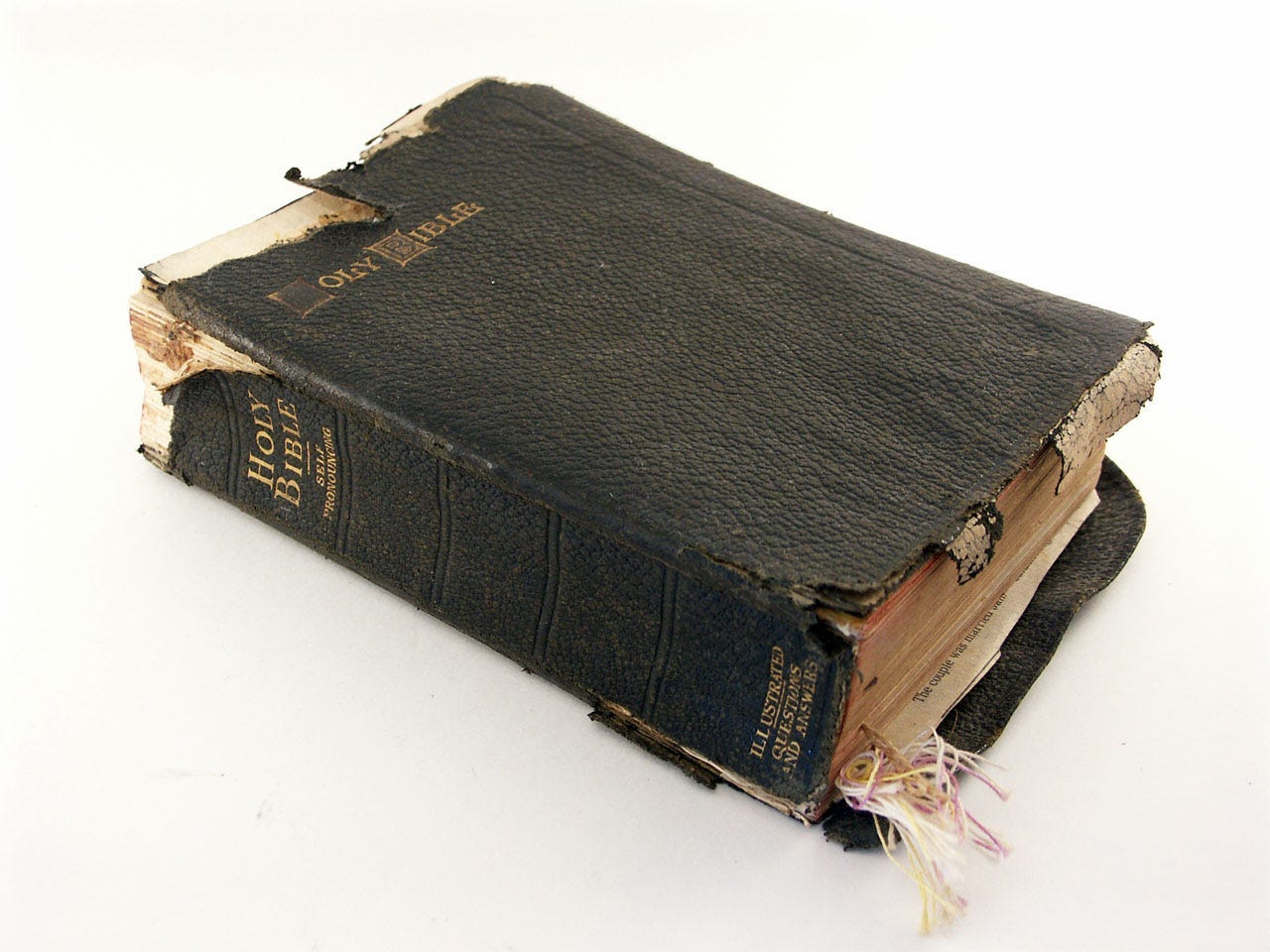

photo taken from www.fusionchurch.cc

Yesterday, following a one of those Facebook comments discussions I find myself in every now and then, a friend sent me a message asking the following question:

Out of interest, what is your position on the Bible then? Do you think it’s God’s Word? Do you think it’s all accurate and God-breathed? Do you think it’s outdated and need modernising? etc

I went to post a reply, but it felt a bit long to bang in the comments. So to go some way to excuse the hour I spent writing the damn thing, warts an’ all, I thought I would put it here where I could at least keep it for my own pleasure without losing it forever among the newsfeeds of social media. If nothing else, it has given me a chance to clear my head — which is exactly why I (occasionally) write this blog. So here it is:

Gosh, well that’s a rather big couple of questions and not ones I feel I can particularly answer with any great authority or absolute conclusion. It’s not really a set of questions I’ve ever really given a written answer to; but I’ve got some time now and I’ll see what I can do.

In terms of its construction, I see it as a collection (or collection of collections) of texts selected by various ecumenical councils over the last couple of thousand years chosen for their sense of religious consistency and usefulness.

Concerning its beginnings and historicity, I think that can (mostly) be found in 2 Chronicles where Josaiah ‘finds’ the Torah (well, probably the Torah) hidden in the temple, confirms its validity, and instigates a huge religious change to his kingdom based on the new monotheism of YHWH. For me, this goes some way to explain the movement away from the Elohim (the Hebrew plural referring to the Council of the Gods) in Genesis 1 and The Book of Job (thought to be the earliest writings in the Hebrew testament) towards the theological apologetics of the monotheism of YHWH (singular) in Genesis 2 and beyond.

Contemporarily, I’d say it is one of the most misread, misunderstood and massively influential texts we have access to.

But I think what you are really asking me is not about the text itself, but about my religious opinions on it as a basis for leading my life: my personal theology, as you might say. Let’s see if I can articulate any of that for you, if you’re really interested.

I think that by ‘God-breathed’ you are asking me if I think the text is inspired by God. To that I would say sort-of-yes-but-among-other-things. I certainly think that the text is irrecoverably intertwined with perceptions of God; After all, almost every single book (except one) includes YHWH as a significant character or influence. But I would also say that there is a significant focus of the text devoted to other concerns — the development of a nation and identity, the construction of law and order, the debate and difficulties of reimagining a religion in the NT. To ignore these aspects would be to belittle them in my mind.

But even there, I don’t feel like I’m properly answering your question. I think that ‘God-breathed’ also implies a sense of authority placed upon the work by a living deity. For me, that is hugely problematic. Let’s ignore the obvious difficulties with the assertion of an existence of a deity in the first place, and instead assume that such a being does undoubtably exist. To be honest, I wouldn’t even know where to start to be able to work out whether or not any particular text or document carries with it the authority of the omniscient. If you would allow me to present a little thought experiment to explain myself:

Firstly, let us assume that the concept of God-breathed also contains the concept of not-God-breathed (if we don’t accept that for now, then we will be discussing nothing more than a tautology and there would be no point in asking the question). Now, if I were to be presented with two texts — one asserted to be ‘God-breathed’ and the other not-God-breathed — what would the criteria be for recognising one as God-breathed and the other as not-God-breathed? Maybe I could test the morality within the God-breathed and not-God-breathed texts against the morality I have found in other confirmed-God-breathed works available to me (ignoring the problem of their own origin). This test would be have validity if the morality of the God-breathed text aligned exactly with the morality of the other confirmed-God-breathed texts. However, that would also undermine the value of the God-breathed text as it would not allow me to learn anything new about the deity, only confirm what is already known. In this way, the new God-breathed text itself would be superfluous to the process of increasing our knowledge of God. Maybe it should just be tested to se if it is similar, but not exact to other moralities in confirmed-God-breathed texts — but then how could we confirm that the nuances between the moralities are themselves God-breathed rather than not-God-breathed?

Even if you are happy with that situation, were we to apply it to the Bible as a singular collection (as I think you are trying to do), then what other text could we test it against?

Maybe the subject of the thought experiment should pray to ascertain the answer. But if their experience of prayer is similar to most (i.e. no lightening bolts from the sky, but rather a ‘sense’ or ‘inclination’ towards the ‘right’ answer), then how could that ‘sense’ itself be tested? After all, very few of sound mind would claim to hear the will of God perfectly. To confirm the ‘sense’ itself as God-breathed, a number of people would also have to undergo the test and come out with exactly the same conclusion. That situation would satisfy me: but it isn’t one that I’ve ever come across in history. Have you looked at the accusations and in-fighting in any of the ecumenical councils? Even today we see people having disagreements on how the will and character of God should be understood (This very debate, for example). One could argue that God doesn’t need us to agree to do his work, or that he reveals himself to different people in different ways — in which case why is an authoritative God-breathed text (still unproven, by the way) even needed or important?

I know that there is an argument we could explore for that and probably another after that as well and that, due to the constraints of time and intellect, what I’ve written is full of conceptual holes — but if I could take a step back for a second (for the sake of trying to preserve a little of my own time today!), I’d like to point out the complexity of even so small a phrase as ‘God-breathed’. I don’t even feel like I’ve begun to scratch its meaning nor logic: and that is only one part of the questions you asked me. My reply has ended up so cumbersome that I would question its use at all — and maybe, by connection, the importance of the question itself in how it should influence my day to day life.

I’ve just started in the journey of raising my two boys. I want to teach them to live well — it’s an innate desire hardcoded into me as far as I can tell. I want them to be good people and when they die, I desperately hope that there will be something there waiting for them after (even though there doesn’t seem to be any evidence or even simply consistent theological agreement on what that might be). I grew up in a Christian household raised on Christian values and it did wonders for me. But in terms of what I can tell my children, I can’t give them the same degree of religious certainty I myself received without resorting to lying to them or dumbing down the truth and pursuit of truth to a degree that it becomes near worthless in my own eyes. I can’t do that to them. For me, the Bible is either too untrustworthy, too incomprehensible in its cultural complexity, or simply too unreliable to ask my children to base their lives upon its vague teachings and gnostic mysteries without hours of the sort of consideration I wrote above. Will it be a part of their upbringing? Yes, definitely: to ignore its influence on our world would be fanciful. But to respect something is not the same as to accept something: either in part or complete. While I feel I can ask them to respect it, I cannot comfortably ask that they accept its content as absolute or even suitably reliable enough to form a significant basis for their own construction of morality and the way they should live their lives. As a result, neither should I model such faith myself.

But here comes the nub and apologetic core of my theology. It was inevitable, I suppose, that any such exploration in so brief a time would distil down to a central core concept in its conclusion. My argument has come to a point where the ‘burden of beneficial outcome’ (if you will accept such a cobbled-together phrase) rests on whether or not such conceptual outcomes are acceptable to a deity figure in a final, inescapable and absolute reality. So here goes:

Let us assume that God does exist and he is good and his revelation to mankind is as obvious and reliable as makes no difference: then I will have taught my children wrong. But I will not have taught my children to do wrong. I hope God would see that I have tried to instil in them an energy to do what is right and to improve the world they see around them. I hope He would see that I have tried to pursue what is good — and even though I may have got it wrong, I hope he is merciful and sees the good and overwrites or re-writes whatever rules and conditions he has placed on existence in order to accept me. If he turns out not to be so forgiving of the ignorant pursuit of good, then I hope that my own feeble attempt at integrity will in some small way comfort me through whatever punishment I am allocated. But I’m not sure if that is a God that any of us would want to follow in the first place.

I hope that all makes sense. I know it is incomplete and full of holes, but I haven’t the time or expertise to properly write it down for now. If you want a TL;DR, then I can give you this reply to your original questions:

‘I think it’s a little bit more complicated than that.’

But that just feels too pithy and a little obtuse for such a subject. I hope that my actual reply is a little more reasonable.